*****NOTE: THIS IS THE COVER STORY FROM THE 2024 SUMMER MAGAZINE THAT WAS PUBLISHED IN THE SUMMER*****

The culture war has always existed in Texas.

At least since 1894 when the Longhorns and Aggies clashed in a scrimmage at Austin’s Hyde Park in the state’s first intercollegiate football game. Admission was $1.

The Seat Geek price for the cheapest ticket to this November’s battle between the two rivals – the first in over a decade – was $555 as of April.

The Aggies vs. the Horns. Farmers vs. Varsity. The Cult vs. the T-sips. The Lone Star State was once split, physically and spiritually, between urban and rural. The team in Austin wearing burnt orange represented the city. The maroon squad from College Station was rural. Texas was parties and protests. Texas A&M was more patriotic and pageantry. One campus was on a sprawling 40 acres. The other in a town with 40 buildings…maybe.

In College Station, a student in the early days of the rivalry woke up to the sounds of Reveille and slept to the tunes of Silver Taps. Located near Sixth Street in the “Live Music Capital of the World,” Texas students lived a life more in tune with the one described by Charlie Daniels in “Long Haired Country Boy.”

Texas’ new highway system bypassed Aggieland in College Station. I-35 connected Austin, and the University of Texas, to Dallas while I-45 was a straight shot from Dallas to Houston. U.S Route 290, which was built in 1927, connected Austin to Houston. In those days, Aggies didn’t populate high society social circles in any of our major cities – that was reserved for graduates of Texas, SMU and TCU. The Longhorns and other alumni from high-tuition institutions inside the Southwest Conference helped pick the wars. The Aggies won them. They were oilmen. Farmers. Ranchers. Twenty thousand of them fought in World War II.

“When I came to Texas A&M from Mississippi College…it was a rough place,” said Frank G. Anderson in 1980, who arrived as an assistant for Dana X. Bible’s Aggies in 1920. “The freshmen had to go through nine months of hazing and a lot of them couldn’t take it. They’d go home at Christmas and not come back. Rough! Tough! Real stuff! Texas A&M! We thought of the boys at Texas as tea sippers.”

The battle lines were obvious, even if reductive. Blue vs. White collar. Flash vs. Grit. Country Club vs. Tent Row. Pick your side.

The burnt orange faithful chose Earl, Ricky and Nobis in Memorial Stadium, the first all-concrete sporting structure in the south when it was erected in 1924. They watched in glee as the Longhorns won three national championships under the direction of Darrell K Royal in the 60s and early 70s, and one more with Mack Brown and Vince Young in 2005. The wishbone offense. Smokey the Cannon. Big Bertha. Matthew McConaughey playing the bongos naked after a win over Nebraska. Texas football helped shape the state’s obsession with the sport.

The 12th Man worshipped Dat, John David and R.C. at Kyle Field. They yelled and hissed as the “College Station Wagon” national championship squad of 1939 led by head coach Homer Norton and “Jarrin’ Jawn” Kimbrough went 10-0. They locked arms and belted the Aggie War Hymn as Johnny “Football” Manziel marched to the Heisman Trophy in 2012. Midnight Yell. The Junction Boys. The Wrecking Crew defenses led by Sam Adams, Von Miller, and others. The Corps of Cadets kissing their dates after scores. No program defines tradition and pageantry like the Aggies.

Both programs cheered for head coach Dana X. Bible at different times – the only man to be the head coach for each of the rivals. BEVO I debuted at the 1917 clash between the two rivals and was a direct reference to the 13-0 win by the Aggies in 1915. Reveille made her way into the rivalry in 1931. Texas leads the all-time series over Texas A&M, 76-37-5. That 39-game advantage exists because of a 14-1-2 run for Texas from 1894-1908 and a 31-3-1 record from 1940-1974.

Ask an outsider about football in the Great State and they’ll list Friday Night Lights and the Thanksgiving Day tradition of Texas vs. Texas A&M as the main cultural identifiers. Our small towns close on Friday nights to watch our high schools battle and then we hunker in front of the television on Saturday for a different type of service – most worship at the altar of Texas or Texas A&M. Football is big here, and that’s the only size we know.

To understand the State of Texas, learn our preferred trinity: Faith, family, football – not always in that order.

With an important interstate battle against Tulane in October 1894 looming, the University of Texas required a practice game as a tuneup. UT student-athlete W.O. Stephens was sent to College Station to organize a team at the Agriculture and Mechanical College of Texas. Frank Dudley Perkins became the head coach and led A&MC to a 14-6 win over Galveston High School in preparation for the contest against Texas, which the Longhorns won, 38-0.

The move forever entwined the two football programs and set the tone for the little brother, big brother narrative that looms over the rivalry. That dynamic solidified further in the most Texan of ways: Oil in West Texas. The sixth and current version of the Texas Constitution was ratified in 1876, and in it the authors ordered the state to create a “university of the first class.”

The state went about setting aside millions of acres of land in West Texas to help fund an endowment for the new school, and that land struck it rich at a well called Santa Rita No. 1 that came in on May 28, 1923. The land now totals 2.1 million acres of West Texas oil-rich land that’s leased out to oil and gas companies with an estimated fair market value of $30.8 billion as of 2022.

Texas receives two-thirds of the money from this Permanent University Fund (PUF). Texas A&M receives one-third. The estimated amount available to the universities for the 2024-25 biennium were recommended to total $3 billion. Texas would receive $2 billion, while Texas A&M gets $979.3 million. The dynamic reached a breaking point when the Longhorns received a 10-year, $300 million contract from ESPN for the Longhorn Network.

From the scrimmage in 1894 to the last stand in 2011, Texas and Texas A&M played 118 times. It was the most played intrastate rivalry game in the Lone Star State until 2023 when TCU and Baylor played for the 119th time. Had Texas and Texas A&M kept playing from 2012-23, the number of games would be at 130 entering 2024, which would rank sixth all-time in college football history.

No coach in series history roamed the sidelines more often than R.C. Slocum, who was an assistant or head coach at Texas A&M for every season from 1972-2022 except for 1981 when he was an assistant at USC. He arrived when Texas was dominating the series with Royal leading the Horns. Over the 30 seasons Slocum wore a headset in Aggieland, he was on the winning side 16 times.

He grew up watching the rivalry as a native of Orange, Texas, and knew how important the game was to the state. He didn’t need a big pregame speech or to ride his team hard during the week of practice. If a kid from the Lone Star State needed help with motivation to face the Horns, they weren’t Aggies in the first place.

“I’d tell the boys on Monday that in the tallest downtown buildings in Houston and Dallas and Fort Worth, they’re talking about this game this week,” he said. “The guys out in the deer blinds of West Texas are talking about this game this week. We get the best seat in the house – we’re in the game. I’m coaching it, you’re playing it, and the whole state cares about the outcome.”

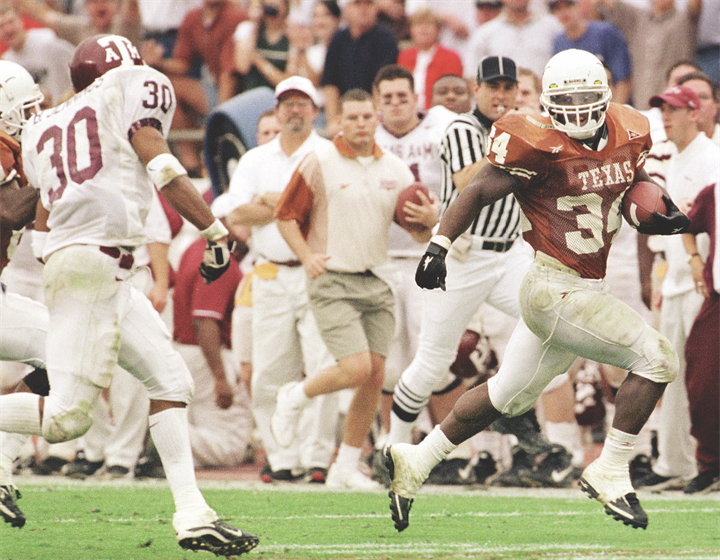

Mack Brown grew up watching Texas play Texas A&M on Thanksgiving weekend in Cookeville, Tennessee. He entered and exited the rivalry as the head coach of the Longhorns in fairytale fashion. His first win in Austin was convincing Heisman Trophy favorite Ricky Williams to play his senior season on the Forty Acres. His biggest victory of the 1998 season was when Williams broke the all-time rushing record in FBS football during an upset win over the Aggies at DKR Stadium.

But even that 60-yard run on Nov. 27, 1998, wasn’t Brown’s favorite memory in the 14 times he faced the Aggies. That came in the last contest between the two combatants when Justin Tucker hit a 40-yard field as time expired in a 27-25 comeback win in Kyle Field. The Longhorns were underdogs in both affairs.

“All I remember is that when A&M was ahead their fans were screaming, ‘SEC, SEC,’” Brown said. “And when we won the game and were walking out, our fans were screaming ‘SEC, SEC’. It is funny to look at it now because both will be chanting ‘SEC, SEC’ this time around.”

Brown jokes that Texas and Oklahoma can’t be played on college campuses because it’d be too dangerous for the opposing team and their fans. That the border war between the Longhorns and Sooners felt different – with more vitriol and hatred – inside the Cotton Bowl than he ever experienced in College Station. He was always surprised when he’d scan the home crowd at Kyle or DKR and see smatterings of maroon mixed with burnt orange, or vice versa, because so many families in attendance possessed split allegiances.

Maybe it wasn’t always that way, but Brown and Slocum saw the rivalry as a brotherly feud more than a territorial dispute. More bragging rights than destruction. The two played golf together with former Texas Tech head coach Spike Dykes in the hills of North Carolina every summer. Brown called Slocum when he was first hired at Texas to assure his old friend that the two wouldn’t be at odds just because they coached at rival schools.

Slocum never saw the rivalry as one rooted in hatred. He hung out with Royal until the legendary coach passed away. He arrived at Texas A&M working for Emory Bellard, who got the job after helping Royal redefine football success in the state and the series. Slocum says he still sees DKR every day because of a framed photo of the two on his desk. The Aggie Bonfire tragedy in 1999 that resulted in 12 deaths brought the schools, and the head coaches, even closer.

“Underneath the rivalry part, there are a whole lot of good people who see the rivalry for what it is – Texans celebrating a sport we love,” Slocum said. “I could never understand why any young man who grows up in this state and has a chance to go to one of these great universities would cross that Red River or go to Arkansas.

“I’d tell every recruit, ‘Pick out which of these two in-state schools (Texas or Texas A&M) fits you the best and you’ll never regret it.”

Realignment ripped the fabric of college football at its seams with the latest rounds kickstarted by Texas and Oklahoma’s decision to leave the Big 12 for the SEC ahead of the 2024 season. Rivalries are the oxygen of college athletics and nearly 300 games of intrastate rivalries between Texas and conference mates Baylor, TCU, and Tech are now void of air.

This phenomenon is not exactly new for college football, but few exoduses cost more in the history of the sport. The Pac-12 folded and two super conferences emerged with the Big Ten and SEC securing television contracts that far outpace their peers. The playoff is expanding to 12 teams and appears soon to bloat to at least 14 to accommodate the third- and fourth-place teams in those inflated leagues.

And while many college football fans, especially the purists, pout about what is lost, a new generation gets to experience the rebirth of a dormant rivalry. The two expected starting quarterbacks when Texas plays Texas A&M on Kyle Field in late November are Quinn Ewers and Conner Weigman. Neither had celebrated their 10th birthday when Tucker hit the game winner to close out the rivalry for previous generations.

But that doesn’t mean the rivalry stayed quiet. Any time Texas played Texas A&M in another sport, the fans cared. So do the players. The rivalry didn’t die. It fell asleep. Ewers and Weigman are thrilled to be part of the group that awakens the beast.

“There is a rich history in that game and it is a heated rivalry, so I’m fortunate and excited to be part of it,” Ewers said. “I grew up wanting to be the quarterback at this university. For it to happen, I couldn’t be more thankful.”

No generation of players endured more changes than the current upperclassmen, including Ewers and Weigman. Ewers was one of the first high school players to forgo his senior year of prep football to cash in on NIL opportunities at Ohio State. The Transfer Portal, a surplus of players eligible because of the COVID exemption in 2020, this level of conference realignment, NIL, further expansion of the playoffs – all maneuvered in real time without a playbook.

Teams on the West Coast now play in a league called the Atlantic Coast Conference. Programs in Los Angeles share the Big Ten with Rutgers. Colorado is back in the Big 12. The NCAA video game is returning because EA can pay players. Each day we move closer and closer to a new inevitability – these guys are employees. The SEC reached a $3 billion deal with Disney (ESPN) in 2020 and the addition of Texas and Oklahoma will only grow the pot moving forward.

Almost nothing about the sport of college football remains as it was when Texas and Texas A&M divorced in 2011, mostly due to previous changes in the model. The landscape is even more unrecognizable if we look through the lens of 1994 when the Aggies and Longhorns transitioned from the Southwest Conference to the Big 12. Bible and Norton probably wouldn’t even know that this was college football.

One thing hasn’t changed, however. Texas vs. Texas A&M is the showcase rivalry of the Southwest. Charley Moran and Gene Stallings knew it. So did Clyde Littlefield and Fred Akers. The yearly game between the Aggies and Longhorns mattered to Joe Routt in 1937 and Pat Thomas in the mid-70s. It mattered for Hubert Bechtol in the mid-40s and Steve McMichael in 1979. And it’ll matter to Ewers and Weigman, and every other person in Kyle Field and the Great State, on Nov. 30.

“It is the battle for the state,” Weigman said. “You want to have that state championship and you’ll do whatever it takes to go get it.”

This article is available to our Digital Subscribers.

Click "Subscribe Now" to see a list of subscription offers.

Already a Subscriber? Sign In to access this content.