Sonny Dykes first met Hal Mumme at Carter High School in Dallas in 1995 when Dykes was an assistant coach at nearby Navarro Junior College. The lack of regulations at the JUCO level afforded Dykes the ability to recruit year around, so he drove an hour northwest up I-45 each morning after teaching a creative writing course to build relationships at known recruiting hotbeds such as Carter, Kimball, and Lincoln.

Dykes was a reluctant entrant into college football. He played baseball at Texas Tech and rebelled against following in his legendary father’s footsteps. His dad, Spike, spent more time with other people’s kids than his own. Such is life as a coach. Dinner wasn’t until 10 p.m. most nights because that’s when Spike returned home from work as Texas Tech’s head coach.

“He’d go watch The Tonight Show and I’d go to bed,” Sonny remembered. “I just didn’t have a desire to coach. My older brother was doing that, too. I was going to do my own thing.”

The family also moved a lot. Sonny was born in Big Spring and then moved to Alice. The family spent a handful of years in Austin before heading out of state for stints in Albuquerque, N.M. and Starkville, Miss. They returned to the Lone Star State when Spike worked in Midland prior to landing in Lubbock.

Sonny, 53, wanted to be a pilot in the Air Force Academy, but his eyesight wasn’t perfect. A few days shadowing a lawyer was enough to know that practicing in a courthouse wasn’t as fun as on a field. At a crossroads, he fell back to familiarity. He fondly remembers a full house after games with fellow coaches and their families mingling together. Family vacations and holidays were also shared with the staff.

“I figured life wouldn’t be much fun without that,” he said.

Sonny formulated a plan to replicate that family feel within a coaching community without all the moving. He decided that becoming one of those Texas high school coaches that sticks at a program for 40 years until retirement sounded like a more stable life to raise a family in than the one he experienced.

He took a job as an assistant at J.J. Pearce High School in 1994 and was planning to join the staff at Southlake Carroll in 1995 before he received an offer from Navarro that he thought was too good to turn down. Navarro offered Sonny a 10-month contract that included $4,000, a dorm room, and free meals.

“I’m thinking 40K a year plus room and board sounded like a great deal,” he remembered. “My first paycheck was $277. I thought I was getting four thousand a month, not total. My car payment at the time was $240. I usually spent the remaining money at CiCi’s Pizza.”

While Sonny grinded away at the JUCO level, Mumme’s new Air Raid offense lit up scoreboards at Valdosta State. Mumme considered Spike a mentor and the pair once spent a week together watching Hayden Fry’s Iowa Hawkeyes and Tom Osborne’s Nebraska Cornhuskers when Spike first took over as Texas Tech’s head coach.

Sonny was back in Lubbock over Thanksgiving when Spike told him that Mumme was moving from Valdosta State to Kentucky. Sonny turned down Mumme’s job offer the previous year but was more than ready to move out of dorms and into adulthood after the 1996 season. Sonny remembers calling Mumme and being shocked to hear that he could join the staff as the wide receivers coach because Mumme’s offensive coordinator at the time, Mike Leach, was going to stay behind as Valdosta’s head coach.

“Hal told me to meet him at the national coaching convention in Orlando in January and by then he’d have it all figured out,” Sonny said. “I drove from Lubbock to Orlando and as soon as I saw Hal inside the convention he said, ‘I’ve got some bad news.’”

Leach wasn’t hired as the head coach at Valdosta State, so he was following Mumme to Kentucky as his wide receiver coach. That meant Sonny could only join the staff as a graduate assistant. The problem was that Mumme offered that job to five other people and only one spot remained because the NCAA lowered GA allotment from six to two since the last time Mumme coached Division I football. Mumme told Sonny that whichever candidate got into school at Kentucky first could have the job.

“I woke up the next morning and drove straight to Lexington,” Sonny said. “I walked into the athletic offices and said, ‘Hey, I’m the new GA. How did I get into school?’ And that’s how I became Leach’s assistant.”

Sonny quickly realized that life with Leach was never boring. Leach decided that he wanted to speak to President George W. Bush, so he called Information after practice and got the number to the White House. Leach called it every day after until one day Mumme hurried into Sonny’s office and told him that some government officials wanted to talk to him about Leach.

“It was the Secret Service,” Sonny laughed. “I guess he had called enough to create a little bit of a worry.”

The Air Raid became Sonny’s rebellion. Spike was a defensive-minded coach who preached togetherness, teamwork, and relationships. He won football games with culture and personality. Leach approached football analytically and cared far more about the X’s and the O’s.

A young Sonny ran headfirst into the Leach School of Football. Dykes followed Leach to Texas Tech and then struck out on his own to preach the gospel of the Air Raid as the offensive coordinator at Arizona. Sonny helped coach record-setting offenses at Kentucky, Texas Tech, and Arizona before Louisiana Tech offered him a head coaching gig in 2010.

Sonny led the Bulldogs to a 22-15 overall record in three years at the helm, including a 17-8 mark over his final two seasons. His Louisiana Tech program won the WAC title in 2011 and won nine games in 2012 to earn Sonny a shot at Power Five football when Cal called prior to the 2013 season.

The four seasons at Cal represented the first true failure in Sonny’s coaching career and a low moment in his professional life. The Golden Bears went 1-11 in his first season and failed to reach bowl eligibility in three of those years. An 8-5 record in 2015 was the bright spot.

The team always scored points. Quarterback Jared Goff threw for a then-Cal record 3,508 yards and completed an NCAA record for most completions in a season by a freshman with 330 in 2013, but the defense surrendered the most passing yards in the history of Division I football. The poor defensive performances continued, and Sonny was fired after the 2016 season.

The struggles at Cal revealed a hard truth every son dreads – the old man was right. The scheme wasn’t enough to win. Cal lacked culture. Alignment. Toughness. Balance. Setting passing records was cool, but winning games would be much better.

“Sonny was more from the Mike Leach school of football,” his sister, Bebe, said. “He didn’t want to do it the old school way. He was the rebel in the family. Once he got that experience with Cal under his belt, he realized that the old man wasn’t that far off.”

Sonny loaded up a U-Haul and drove back to Texas, stopping in Las Vegas with his best friend along the way. He was mad, and humbled. The Air Raid by itself wasn’t the route to college football success. He needed a defense that could match the offensive output. He also learned how much Texas meant to him, and his family.

“We know now where we belong,” his wife, Kate, said. “We tried and I’m glad we did because I think he would’ve always wondered what if. He is like Leach that way. He has a wandering eye, the opposite of Spike.”

The secret to success became obvious. Sonny needed to combine the scheme he picked up from Mumme and Leach and combine that with the values and culture that he watched his father overachieve at Texas Tech with for all those years. Add in Texas talent and an administration that believed in the power of football for young people and maybe redemption wasn’t too far away.

“They are the two most different people in the entire world, but they were remarkably similar when it came to the way they viewed the game,” Sonny said about his dad and Leach - the two biggest male figures of his lifetime. “I see myself as a combination of the two. More from Mike’s school on scheme, but more on my dad’s side when it comes to team building and culture.”

TCU head coach Gary Patterson called Sonny as he made that trip from Cal back to Texas. Patterson offered Sonny a role as an offensive analyst. The opportunity allowed Sonny to raise his family in Texas and get a microscopic view on how a defensive-minded coach ran a program in the modern era.

“The most important thing I learned is that we were doing it right at Cal,” Sonny said. “There wasn’t some magical formula. It allowed me to get my confidence back. Those principles that allowed us to be successful at the other places can still work. It was just a matter of finding a place that was aligned.”

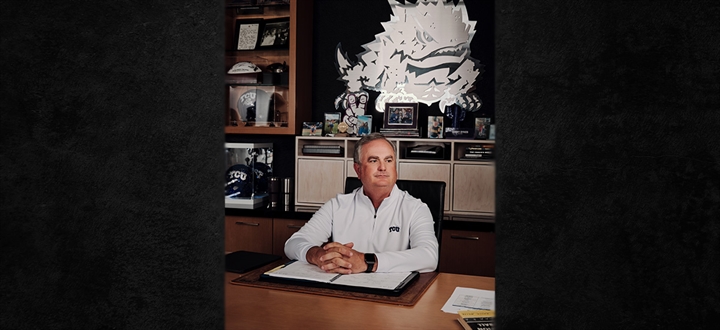

Dykes loaded the bus alongside his brother, Rick, and laughed. Hours earlier TCU upset mighty Michigan, 51-45, in the Fiesta Bowl to earn a trip into the championship game of the College Football Playoff. A title clash fittingly set in Hollywood because the Horned Frog’s run to the sport’s biggest stage was ripped from a script.

“If Spike was here, he’d get a kick out of this,” Sonny and his brother recall saying to each other.

TCU was 16-18 in the three seasons preceding Dykes’ arrival in Fort Worth. Only three players on the entire roster played a college football game after November before beating Michigan in Arizona. The Wolverines are college football’s most winningest program. The Horned Frogs were in the Mountain West Conference at the start of last decade.

Sonny didn’t know much about TCU when he arrived in Fort Worth as an offensive analyst for Patterson in 2017. The Horned Frogs weren’t in the Big 12 when Sonny was an assistant at Texas Tech earlier in the century. He was surprised at the quality of the facilities and the overwhelming administrative support. Sonny was always a fan of DFW, dating back to when Leach sent him to the area to recruit in 2002.

“I remember thinking, ‘This is one of the best 25 jobs in college football, and probably a lot higher than that,’” Sonny said about his first stop at TCU. “I always assumed Gary Patterson would coach here until after I was retired. Never even considered that this job would be available or open.”

Dykes went across the metroplex to rival SMU and retooled the Mustangs into a legitimate contender for the first time since the Death Penalty in the 1980s. The man who used to hang out at south Dallas high schools as a young assistant at Navarro Junior College was now helping SMU integrate itself back into Dallas culture. His Mustangs were on the cutting edge of the transfer market and advertised themselves as Dallas’ team.

And they also started beating TCU. As SMU’s star rose, the sun set on Patterson’s tenure in Fort Worth. The same thing happened with Mack Brown at Texas and R.C. Slocum at Texas A&M. The same message is hard to send for 20 years, which is why kids move out of their parents’ house at 18. TCU’s new athletic director, Jeremiah Donati, was the Deputy AD when Sonny was an offensive analyst in 2017. Donati still has a voicemail that Sonny left him following his appointment as AD. In that voicemail, Sonny tells Donati to let him know if he could ever be of service. It turns out, he was.

“When I was driving to interview him, I remembered that voicemail,” Donati said. “Sonny was a step ahead of the other candidates because of his local ties and proof of concept at SMU with bringing in the community. We saw firsthand what he was doing, and the ways in which it was hurting us.”

Winning is achieved in a variety of ways. Sonny knew that better than most as the youngest son of a legend and the protegee of another. TCU won a lot of football games in the Patterson era under rule of an iron fist. Sonny took a softer approach. He instilled a culture his dad would be proud of and meshed his Air Raid passing principals with a coordinator who had extensive background running the football. He did the same thing at SMU when he hired Rhett Lashlee to be his offensive coordinator from the Gus Malzahn tree.

The players immediately bought in. Roster turnover is normal during coaching transition, especially during the portal age. Sonny kept the best players at TCU on the roster and left spring optimistic. His team was experienced and mature. The offensive line was in great shape. He felt he had two quarterbacks capable of winning in the Big 12. But no one could believe a 12-0 start and a trip to the College Football Playoff was in the cards.

“The expectation was to get back to a bowl game because we hadn’t done it in a few years,” Donati said. “Let’s get back there, whether that is six wins or nine wins, to reestablish TCU football. Coming out of spring, my expectations started to rise.”

Leach passed away on Dec. 12, 2022, days after TCU qualified for the College Football Playoff. The win against Michigan made Sonny the first disciple of the Air Raid to reach a national championship game in the CFP era. The Horned Frogs beat the heavily favored Wolverines in an old-fashioned Big 12 shootout that Leach would’ve loved. The game also featured a pair of defensive touchdowns as an ode to Spike.

Sonny had done it. He combined the schools of thought. And he had done it in his home state and with his family at his side. Like many great explorers, Sonny had ventured out in search of meaning and individualism, only to return home to find it right in front of his face. He’s building his own legacy outside of the shadows of Spike or Leach or Patterson. His wife and sister say he’s becoming more like Spike with each passing year, but Sonny isn’t quite sure. Maybe it’s his last act of rebellion.

“My dad was comfortable in his skin. He was who he was. I’m still navigating that,” Sonny said. “I’ve had so many diametrically opposed influences on me that you go, ‘Okay, what are you really?’ I’m a mutt in some ways.”

This article is available to our Digital Subscribers.

Click "Subscribe Now" to see a list of subscription offers.

Already a Subscriber? Sign In to access this content.