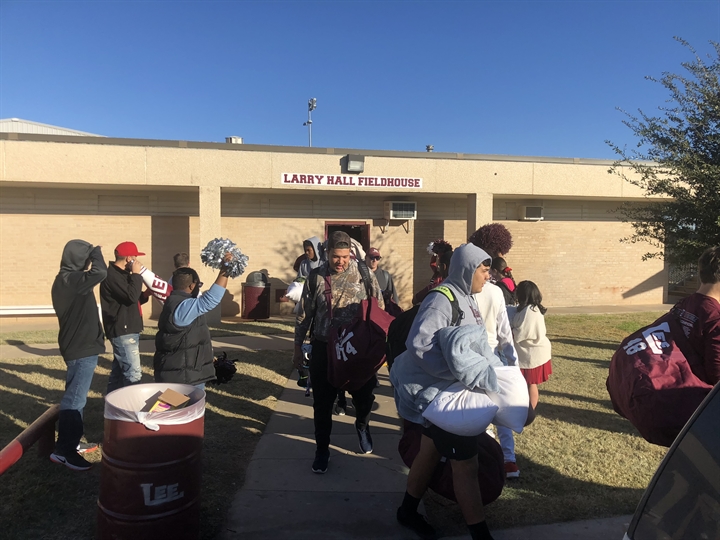

Larry Hall always asks himself the same question when he gets to the Midland Legacy fieldhouse at 4:00 a.m. and peers up at the sign above the entrance.

“It’s my five minutes of fame every morning,” Hall said. “It’s a feeling where you ask yourself, ‘Did I really deserve it?’”

No one is there to answer that question for him as he stands in the dark. The scalding West Texas sun hasn’t even surfaced. There’s not a coach in sight, and the players presumably haven’t woken up yet. So the 82-year-old Hall is left to ponder if he truly earned this honor as he unlocks the door with the key Legacy head coach Clint Hartman gave him.

He’s the first team member to arrive, and he’ll surely be the last to leave that night.

“Whenever this is all said and done, he’s going to have been in that fieldhouse more than anyone has ever been in their life,” Hartman said.

Hall hasn’t been paid a dime in the three decades he has volunteered for the Midland Legacy (formerly Midland Lee) program. He’s worked for five different head coaches, seen the first three-peat state championship run from 1998–2000 and three-straight losing seasons from 2014–16. He’s shown up every day no matter what the team’s record was. He’s loyal to the program.

That’s why he’s walking in the door of the Larry Hall Fieldhouse at 4:00 a.m. to do laundry.

…

Lee head coach Earl Miller was tired of dealing with tapes for his games.

Miller took the job in 1986, and after a grueling practice in one of the first seasons of his tenure, Miller sent a player to bring him Larry Hall. Hall had three kids who attended Lee, two daughters who danced for the Dixie Dolls drill team and a son, so he watched the team practice with the other die-hard fans after he got off work.

The coach asked Hall if the rumors were true. He’d heard Hall had just gotten a brand new video camera, and he wanted him to film the football games for him thinking it’d be easier than old-fashioned tapes.

Miller didn’t know at the time that he’d secured a commitment for a steadfast volunteer for the next 30-plus years.

“I said, ‘Well, I’ve never done it before, Coach, but I’ll video the JV game Thursday night and see how it works,’” Hall said. “I’ve been doing it ever since.”

Hall took on more responsibility with each head coaching change. As his children went to college and got married he started looking for more ways he could help out the younger coaches with their long days so they could get back to their families at night. He doesn’t venture into any game planning or football strategy, but he ensures the program runs seamlessly.

During the season, Hall gets to the fieldhouse every morning at 4:00 a.m. and pulls all the players’ laundry clips out of the dryer before hanging them up in their respective lockers. It’s a race to 6:00 a.m., when a chunk of Legacy players come into the facility to get a morning lift in.

After the gear has found its rightful owner, Hall goes to the cafeteria to retrieve the team’s breakfast. All of the players are required to come through the breakfast line before morning practice so they can be accounted for. Hall knows every player by name and face because he needs to check them off as present. For the athletes that don’t show, Hall writes their name on a notecard and texts it out to the coaching staff so the coaches can confirm if the kid had an excused absence they disclosed, or needs to be corralled and disciplined.

The best part of the day is when Hall gets to pull up his lawn chair with his other friends, affectionately termed, “The Old-Timers Club”, and watch the boys practice. The group makes it to every session and shakes hands with all the athletes when they come off the field, encouraging them for the upcoming Friday.

“I have to watch practice of course. I couldn’t miss practice,” Hall said. “That’s the most important thing in the world is to get to watch practice.”

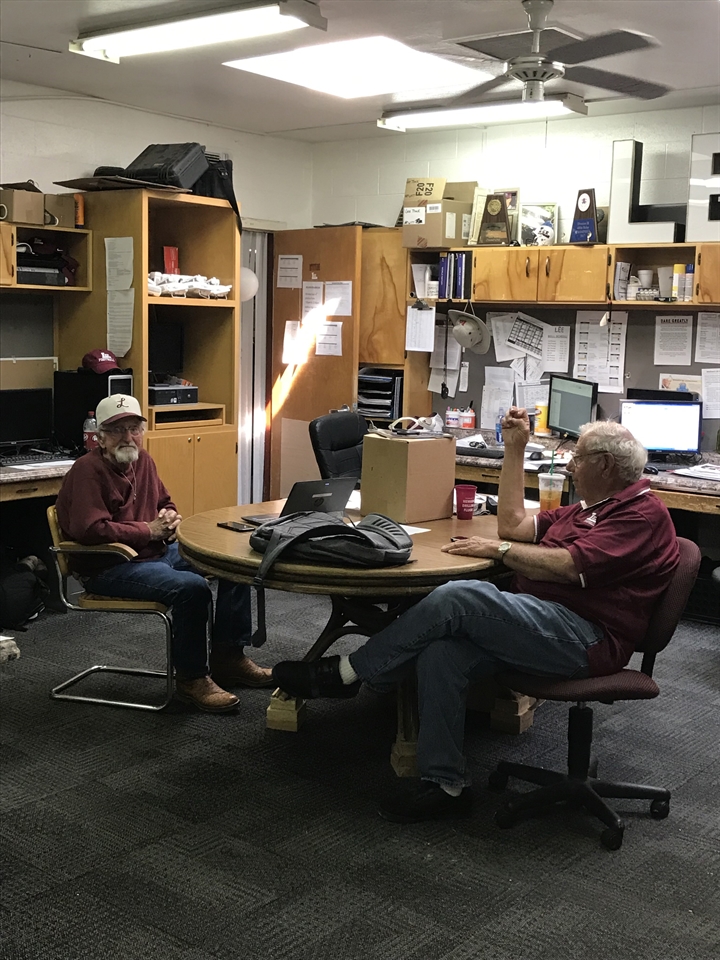

In between the morning and afternoon practice, Hall does anything he can to help out. He takes pride in mowing the lawn and hangs up every sign in Hartman’s office and in the locker room. When there’s a lull in the day, Hall and Hartman hold court in the coaches’ office, where coach can let friend know what’s on his mind and friend can give coach clues about certain kids he should check in on.

“I can tell him the things that are bothering me and I know it’s going to stay right there with him. I don’t have to worry about him going out and telling the community how I felt that morning,” Hartman said. “He can also give me hints on those kids that check in, like, ‘Hey, that kid’s been a little different lately.’ He can see how they are and how they interact and change.”

Once the afternoon practice concludes, Hall grabs all the players’ dirty equipment and throws it in the washing machine. He doesn’t usually get home until about 10:00 p.m. at night.

“I love the kids and love to be around them,” Hall said. “It makes a difference if you watch the football game and you know the players out there. You know the individuals. It’s great to see them develop.”

Technically, Hartman assigns assistant coaches to take care of the laundry every week, but Hall doesn’t pay attention to it. The laundry is his terrain, and no one else is allowed to help him.

“One of our coaches last year was trying to beat him up here to do the laundry because it was his week,” Hartman said. “Mr. Hall got on him. I told that coach, I said, ‘Don’t mess with him. He’s got a routine,’ I don’t mess with it.”

Hartman describes Hall as a selfless leader because his efforts make it so the coaching staff can get home sooner to their families every night.

“He’s probably saved more coaches’ marriages than people understand over those years because (he does) little stuff like taking on laundry,” Hartman said. “For them to be able to walk off the practice field late after our long school day and go home at 7 pm and see their family before they go to bed, that’s because somebody’s not having to do laundry.”

He’s never suited up for the Rebels or donned a coaches’ headset, but his diligent work ethic has earned him a spot in the Midland Legacy family. Truthfully, he knows more about the program than anyone else there.

…

When Hartman and his staff took over ahead of the 2016 season, they took one look at the coaches' office and wanted to make a change. The giant table needed to go.

The office wasn’t big in the first place, and the beige table in the middle of the room was so sizable there was just enough space to pull out a chair and sit in it. It was old and it barely fit. It was a no-brainer to chuck it.

Hall squashed the idea instantly. That table had been there since 1980 when Spike Dykes was the head coach. Dykes led Lee to their first state title appearance and compiled a 34–12 record over four seasons before going on to become the winningest head coach in Texas Tech history. It had been there for every state title in Lee history, and it was as permanent in the coaches’ office as the walls themselves.

“They’ll get rid of me before that (table) goes,” Hartman said.

So just as Dykes and his staff talked shop at the oversized table back in 1980, Hartman and his staff strategize on how to win football games today. But there’s so much more than football discussed at the table.

Hall sits there every morning as he’s checking off kids on his list, looking all of them in the eye and saying, “Good morning!” It’s where he notices changes in the players’ moods, or if they aren’t eating breakfast for an extended period of time. It’s where Hall talks to Hartman when the players are out of earshot and tells him who to check in on, and it’s where the coaches have a good laugh in the middle of the day because they’ve been there since before the sunrise.

“The one thing I’ve always thought is the greatest representation of family is when they sit around the table and they pray together,” Hartman said. “Well that table is a symbol of that.”

Hall is a friendly face the Legacy football players see every morning, squeezing by the giant table to pick up their breakfast. He’s one of the most popular adult figures at the school, someone who keeps up with the players even after they’re done donning the Legacy maroon.

“They may not know every coach they’ve had in their life, but I guarantee they know who Mr. Hall is,” Hartman said. “They see him in the neighborhood and they tell him, “Hello.” He probably has more relationships because of the 30-plus years of him doing this than anyone connected to the Midland Lee/Legacy program.”

One of those players is Felix Hinojosa, the team’s former starting quarterback in 2018. Hinojosa picked up breakfast from Hall for four years and formed a relationship with him as he led the Rebels to a 9–3 record his senior year. No matter what the team’s record was, whether they were winning playoff games as Hinojosa did or whether they had a losing season, Mr. Hall was consistently there for them.

“He never changes, so it’s kind of special,” Hinojosa said. “He’s very loyal to the program and he’s very respected. (The players) know in the morning he has breakfast for us there and he does it all out of the kindness of his heart and with a good attitude.”

And much like Hall helped out Hinojosa and the Legacy football program, Hinojosa wanted to give him a helping hand.

Hinojosa is the owner of Armor Landscaping in Midland, which services commercial and residential properties and even dabbles in industrial lawns. Hinojosa recently added Hall to his client list. He offered to mow his grass for free, considering all the time Hall spent over the years mowing the Legacy yard. Hall refused the offer, insisting on supporting Hinojosa’s business.

“He wants to do it the right way like anybody else would,” Hinojosa said. “He’s a really good person. He’s genuine.”

Hall doesn’t accept any handouts, and he hardly accepts any thank yous for the job he does. He just wants to help out.

That’s why Hartman couldn’t let Hall find out about his plan to rename the fieldhouse after him.

…

Hartman told two people about his plans to rename the fieldhouse after Larry Hall at the 2018 football banquet. The first was his oldest daughter, Madison, who now plays basketball at Hardin-Simmons University.

Madison was on the sidelines every Friday night with her father, and both father and daughter were very close to Hall. The coach needed his daughter to help him in rounding up Hall’s family so they could surprise him at the banquet when they announced they were renaming the fieldhouse after him.

With three weeks until showtime, the coach called one of Hall’s daughters that lives down the street from the school.

“I asked, ‘Can we get it done in three weeks?’” Hartman said. “And she said, ‘Yes, we can get it done coach.’”

So Hall’s daughter called her siblings, her brother who lives in Midland and her sister who lives in Frisco, Texas, and let them know what was happening. They all made it to the banquet three weeks later. Hartman made another call and got John Parchman, the coach who won three State Championships with Lee, to come in support.

All of this was unbeknownst to Hall.

For the past 15 years, Hall has given out the “Rebel for Life” award at the team’s banquet. It’s a symbol of people who have bought into the program and become a part of the program’s family. That night, he was set to give it out to an assistant coach. Or at least that’s what he was told was going to happen.

“I was sitting there at the table and I made a comment to the people around me, ‘Look at (the coach) over there, he doesn’t have a clue what’s going to happen to him.,’” Hall said. “And I had a few snickers and I didn’t realize they were saying, ‘You don’t know what’s going to happen to you either, young man.’”

When Hall went up to present the award, Hartman surprised him with his entire family and the announcement that the team’s facility would be renamed the “Larry Hall Fieldhouse”. Hinojosa was in the crowd that day, and he can’t think of a more fitting honor.

“I’m really glad that they did that for him because I don’t know that everybody knows the sacrifices that he makes,” Hinojosa said. “He gets the coffee ready for the coaches and he’s washing all the clothes, making sure everything is good to go and stuff that really helps out. It’s stuff that doesn’t get noticed unless it’s not being done.”

Nearly four years later, Hall still asks himself every day if he deserved it when he shows up at the Fieldhouse and looks at the sign before the sun rises. For three decades he’s mowed grass, picked up laundry and filmed football games for free. And he’s done it because he wants to help, because he’s cared about every one of the hundreds of kids over the years who’ve come across his face at breakfast and because he wants to make the coaches’ lives a little bit easier.

“I think he’s a great representation of what this world could be,” Hartman said. “If people were more like him and sharing and didn’t see color and didn’t see socioeconomics and just wanted to help people? How much better would we be?”

So the reader can judge if he deserved it, because the Midland Legacy family already has.

This article is available to our Digital Subscribers.

Click "Subscribe Now" to see a list of subscription offers.

Already a Subscriber? Sign In to access this content.