If you have a chance to look up toward the heavens today, give it a second and you might hear the faint whispers of a man yelling “Who Believe?” as he did so often around Orangefield, Texas.

Go ahead and shout back “We Believe” if you’re able. It would mean a lot to the Coulters.

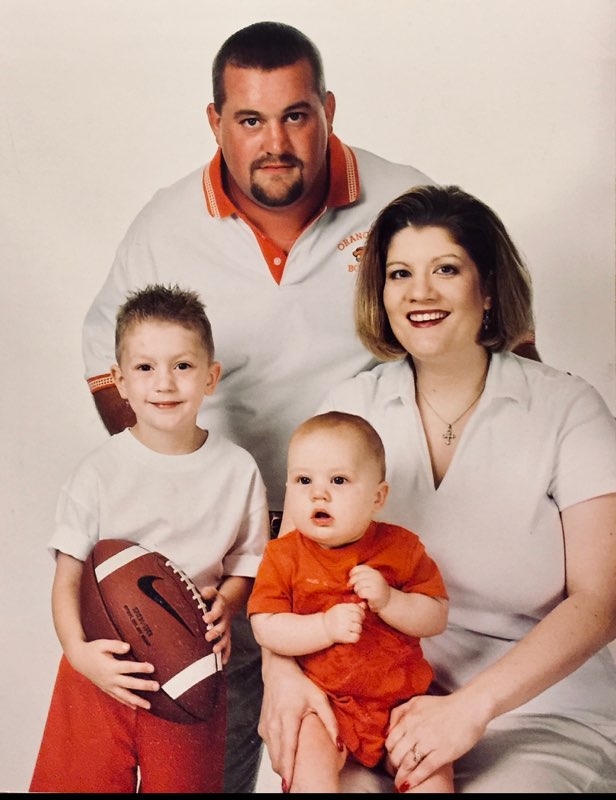

Chad Coulter is no longer with us; he succumbed to his battle with Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma shortly after the 2019 football season. But his memory most definitely lives on in the tight-knit community 25 minutes east of Beaumont.

Coulter bled orange and white. He grew up a Bobcat and proudly wore the No. 72 as he became an all-state offensive lineman before going off to play at Kilgore College.

He was known around town as the man that would yell the first part of Orangefield’s school motto, “Who Believe?”

Someone that most definitely does is his son Coby, a junior-to-be who wears the same number and plays the same position in honor of his pops.

“He was a nice guy who cared for everyone in Orangefield,” Coby said. “He really loved the people around here. He loved being around people. He loved all of us, the whole family.”

Chad did a bit of everything in the Orangefield school system. He coached track, was the junior high boys athletic coordinator, was an offensive line coach at the high school, taught science.

“Hell, at one point he was the assistant softball coach,” said Josh Smalley, Orangefield’s head football coach.

He didn’t stop coaching football until he had a couple of heart attacks.

“When he got done with stem cell therapy the doctor told him he needed to take two to three months off. But he loved going to work,” said his wife, Heggie Coulter. “He loved being with those kids. He was in everything.”

Added Smalley: “He never complained. I’m sure there were days when he would go and get chemo in the morning and then come to practice after school, and I’m sure he didn’t feel like doing it but did it because he loves the kids. Never heard the guy complain. He was a happy-go-lucky guy.”

He battled cancer for over three years until it reached his brain. The doctors told his family they could try to treat it, but weren’t sure if it would do any good. He got more treatments, but by September, it had returned strong enough to paralyze half of his face.

“Then in October it paralyzed the other half of his face,” Heggie said. “We knew in November that he didn’t have much time left.”

Despite all of this, Chad was there to watch his son at every Orangefield game except the Bobcats’ bi-district playoff loss to Franklin.

“He would always show with his actions,” Coby said. “He’d always lend a helping hand to anyone in need. He was always there to help.”

As you could imagine, the perseverance that Coby showed through all of this was as inspirational as any motivational speech Smalley could have ever conjured up for his team.

“To be a sophomore in high school and deal with the death of his father, I can’t imagine what he had to go through daily,” Smalley said. “To have your dad battle cancer and you still have to be a kid and go to school, go to football practice and play in a game, he is a special young man.”

The impact that Chad had on the community was nowhere more apparent than at his funeral. Over 500 people showed up. Athletes stood for the entire 2-hour service with their finger in the air. Coaches, trainers, co-workers, high school and college teammates shared memories instead of the traditional eulogy.

“What Chad Coulter means to this school district and this community you can’t put into words,” Smalley said. “Everybody that has taught, coached here or played here reached out and loved the family.”

His word for the school year was “Live.”

“This meant more to him than staying alive,” Heggie said. “He wanted to inspire others to live each day to the fullest no matter what obstacles they faced.”

That’s a message that Coby lives by every day.

“It made me want to be a better person and to always put others before yourself,” he said.

After Chad’s passing, students started a petition to name the stadium after “Coach Coulter.” It had about 2,000 signatures before COVID-19 put things on pause.

“He was the epitome of what it means to be a Bobcat; toughness, hard-worker, no fear,” Smalley said. “He definitely put that into his kids and family.”

Boy, did he.

“He would always tell me that I couldn’t guard him,” laughed Coby, who could squat 425 as an incoming freshman and can now squat 600 pounds. “I would have taken him easy.”

Who believe?

This article is available to our Digital Subscribers.

Click "Subscribe Now" to see a list of subscription offers.

Already a Subscriber? Sign In to access this content.