SAN ANTONIO and MOBILE, Ala. — Sometimes it would be a pair of bright blue socks — or a mismatched pair. Sometimes it'd be an outfit that appeared to be waging war against itself.

"I'd think it was the coolest thing," he said.

A preteen Marcus Davenport would come down the stairs and his dad, Ron Davenport, would greet him with a raised eyebrow and a quizzical look on his face.

"Uh, are you sure you're going to wear that?"

Marcus would chuckle and keep walking. But his mind would race. He'd get home from school and the outfit would come off — and never reappear. His dad never told him to take it off. But he felt the pressure of the question's tone.

It was frequent, playful ribbing. But eventually those outfits stayed on and even after prodding from his father, some would make a reappearance.

"He just taught me to be myself," Davenport said.

A decade later, he's exactly that.

His favorite poem he's written argues that too closely analyzing that which enthralls us takes away from the subject's charm and allure. It's called "Beauty."

"We limit it and mold it into things we can understand when, true beauty, you shouldn’t have to fully understand it to appreciate it," Davenport said.

His love affair with video games dates back to Kung Fu Chaos and The Elder Scrolls: Morrowind on the original Xbox, where he played with a fully customized character with unlimited stamina and magical powers.

"It was something I got to create," he said. "I always thought that was cool."

These days, he leans more toward Fortnite, Minecraft and Shadow of War, another role-playing game.

He's a diehard fan of anime classics like My Hero Academia, Naruto, Dragonball Z and Attack on Titan.

"People just create these imaginative worlds," he said. "I always find that crazy."

One NFL team asked him in an interview if he'd ever made a trip to Comic-Con. He hadn't. San Antonio's annual edition of the event always takes place during football season.

He'll bury his nose in comic books and graphic novels, but he's just as likely to sit down with one of the works of Carl Jung, one of the founders of psychology. For over a year in college, he found himself reading Robert Greene's The 48 Laws of Power repeatedly before gifting his copy to a graduate assistant, just as an ex-teammate gifted the book to him.

"Dad put his identity on us, but left plenty of space for us to find things we like and we want to do," his younger brother, San Antonio Stevens junior Michael Davenport, said.

And next month, Marcus will be a first-round pick in the NFL Draft, with a chance to go as high as the top 10.

After four years at a fledgling UTSA program — one with just a single NFL Draft pick in its seven-year history — he's among the best prospects from the state of Texas in this year's draft. Heisman Trophy winner Baker Mayfield might end up being the only Texan drafted higher.

"He has as much upside and room to grow as any player in this draft," an NFC scout told Dave Campbell's Texas Football. "He just has a lot of work to do to get there."

He's spent nearly all his life in San Antonio, but he's about to begin a new one as an overnight millionaire. He's a couple signatures away from trading in Betsy, his decade-old white Acura sedan, for a new Ford F-150 Raptor.

"When you’re 6-7, you’re kind of limited. You ain’t fitting in any of those Italian jobs," Ron Davenport said.

His road to 6-7 was trickier than most. He was less than four pounds when he was born. For most of his life, he eyed a future in the NBA. He spent most of his football career at receiver. He graduated high school with a 198-pound frame and three Division I offers. Power 5 programs inside and outside the state wouldn't return his calls.

Now, he's one of the most coveted pass rushers in the 2018 draft class.

- - -

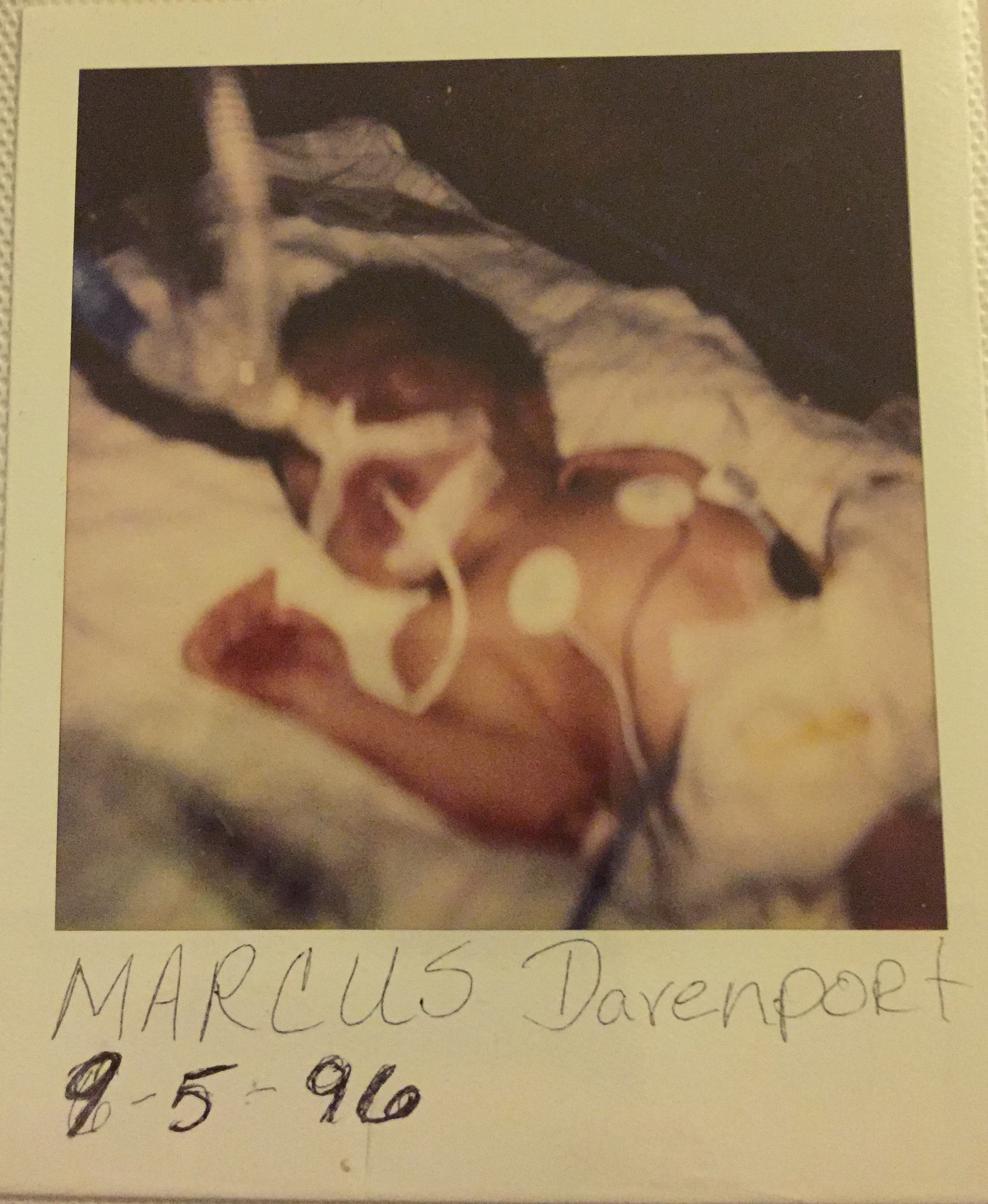

Ronnetta Davenport was barely into the third trimester of her second pregnancy when her water broke. She quickly made her way to Wilford Hall Medical Facility at Lakeland Air Force Base, but doctors couldn't keep Marcus Davenport from making his premature arrival.

Doctors were forced to deliver him through dry birth.

"They had to basically pull him out," his mother, Ronnetta Davenport, said. "And when he came out, he looked like Mike Tyson got a hold of him."

The parts of his body that weren't yellow with jaundice were black and blue with bruises. At just three pounds and 14 ounces, he easily fit inside the palm of either parent's hands. For the first day and a half of his life, machines breathed for him while his lungs developed. He spent the first 10 days of his life with a tube shoved down his throat, reliant on Ron Davenport to provide valuable, invigorating nutrients through a feeding tube.

The underdeveloped liver that that turned him yellow from jaundice required phototherapy treatments that required his fragile eyes to be covered while powerful fluorescent light performed the function his liver couldn't yet complete.

He'd somehow manage to scoot his slight body into a corner of the incubator, forcing nurses to cover his knees with gauze. He'd rubbed his paper-thin skin raw.

Doctors warned his health would get worse before it got better.

"But he never got worse," Ron Davenport said.

Three weeks later, at six pounds and 10 ounces, he was able to go home to the Davenport's 2,100 square-foot home in west San Antonio. Two years later, his parents divorced, leaving Marcus to split time between his parents until his mother, who moved to Omaha and now lives in Houston, began undergoing treatment for uterine cancer in 2005. His nurturing side showed on those visits. When he was eight, Marcus woke his mom up on Mother's Day with home-cooked breakfast — eggs, toast and a cup of hot chocolate — and a foot massage.

When she'd visit San Antonio when he was in high school, he'd put homework off for a couple hours after school and trade game film for Orange is the New Black on Netflix while they sat and talked on the couch.

His father spent most of his life in the Air Force and works IT in medical systems at Lakeland. He emphasized grades and chores — Marcus was responsible for mowing the lawn and doing the dishes. Sunday mornings were reserved for the family to clean the house together.

"I always told him, 'If you can deal with me, you can deal with anybody,'" Ron Davenport said.

He wasn't strict, but expectations were clear. Do what is asked of you at school and at home and you wouldn't have problems.

Marcus and his brothers found a family tradition in making trips to the movies. Debates ignited before they could even get back to the car. Pulp Fiction, Fight Club and Interstellar are among his favorites, but he's got a soft spot for science fiction, too. He smiled and sat up when asked for a review of The Last Jedi, one of his recent trips to the cinema before leaving home to train for the draft in San Diego.

"That movie is for the new generation. They’re cutting some ties to start in a new direction," he said.

"I liked most of it, just not the Leia thing. How’s she going to just float out in space, come back and be alive?" Michael Davenport said.

"She got the force, man! She got the force! Luke can’t be the only one out here doin' stuff," Ron Davenport said.

By age four, some family members noticed Marcus pronouncing some letters oddly and speaking at hyperspeed. He spent the next four years in speech therapy until he caught up with his peers' development and didn't need it anymore.

"He was always behind--developmentally, physically behind. He had a lot of people working with him to get him on track," Ron Davenport said. "He probably didn’t really get on track with everything until he was about seven or eight. Then I had to put him up two age groups for him not to be the biggest guy out there in his age group."

As a young grade schooler, he'd pop and lock along with the Michael Jackson hits his dad cued up and boomed through living room speakers. His boundless energy earned him the nickname, Human Halftime Show. He'd jump on and off the brown leather sectional that dominates the space in the living room and served as the setting for two decades worth of stories. That side of his personality, inherited from his mother and her mother, has gone dormant as Davenport grew into a man. He's quieter and more reserved now. He greets questions with a "Hmm," a rub of his chin and a brief silence before offering concise answers.

"I don't really like — or didn't like — interviews," Davenport said. "It wasn’t a New Year's resolution exactly, but this was something I decided I should try: Do one thing I fear every day. So that's why I'm here talking to you now. Speaking things into existence and disclosing myself leaves me vulnerable."

He's already gotten questions from NFL teams about his love for football after committing the unforgivable sin of having interests outside of the game. He crammed 18 hours into his final semester at UTSA so he could graduate and focus on preparation for the draft instead of taking classes in the spring. Coaching, teaching or a political career wait on the other side of the field. And the photo album back in San Antonio that tells the story of his life has a lot of more photos of him with a basketball in his hand than with a helmet on his head. But for now, football is the focus.

Still, he winces and dismisses questions from NFL teams about whether or not he really loves football.

"You should watch my film," he tells them.

They'll find 27 tackles for loss in his final two seasons under coach Frank Wilson, including 17 with 8.5 sacks in 2017 on the way to becoming Conference USA's Defensive Player of the Year.

At the Senior Bowl in January, he sacked Mayfield and scored a touchdown on a 19-yard fumble return.

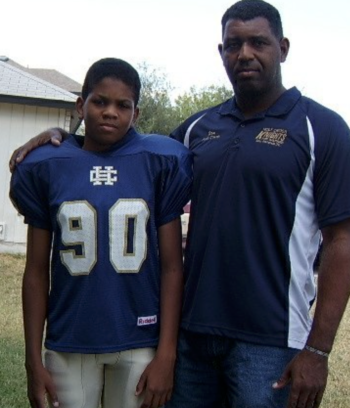

Just six years ago, he was a mostly anonymous receiver at San Antonio Stevens who had spent his entire career with the ball in his hands. His coach, Darryl Hemphill wanted to move him to defensive end.

"Dad. Was. Livid," Hemphill said. "I said, Mr. Davenport, all I can ask you to do is trust me." The Falcons had a run-heavy offense and Hemphill didn't want one of his most promising athletes standing out on the edge of the field "looking pretty."

"You get to come off the ball every play, you get to swat, swim, sack, you get to turn counters inside out. It’s going to be fun," Hemphill told his then-high school junior. "You used to use your long arms to go get the ball and catch it and get hit. Now, you use them to separate from a blocker and go hit somebody."

His eyes got big. He was sold. Davenport went home and Googled the best player at his position in his class.

He found Da'Shawn Hand's name and showed the future two-time national champion at Alabama's profile to his dad.

"Marcus, that guy's 6-4 and 250 pounds! You're not even close to that," Ron Davenport told his son.

Davenport spent his junior season at Stevens deflecting multiple passes a night. When Hemphill gathered his team to review game film, Marcus would sit silently. The frank criticism from a mistake or the pats on the back for a big play would both earn subtle nods and a 'Yes, sir."

He just wanted to know the answer to two consistent questions: why and how any particular play landed in the "good" or "bad" columns. Before long, he got frustrated and noticed opponents refusing to run plays to his side of the field.

Davenport had a lot of room to grow when he first set foot on a college football field. (Photo by Mary Scott McNabb)

"I'd tell him, 'That’s a compliment, Marcus. They don’t want to run that way. Would you run toward you? They’re running the other way and now we can put our best linebacker behind our other defensive end. You're helping the team," Hemphill said.

"Marcus was never better than everybody else growing up. He was probably even a little bit behind. It’s good for him to not know how good he can be yet."

Any NFL team shopping for a pass rusher covets him now, but when he looks in the mirror he still sees the scrawny kid waiting for recruiting letters that would never arrive.

He drew modest attention from college programs, even after a strong junior season. Incarnate Word, a San Antonio FCS program that began play in 2009, offered him a scholarship, but only New Mexico and UNLV followed with heavy, late recruiting pushes.

UTSA mostly ignored Davenport until late in the process, inviting him on campus for a visit his senior year.

Coach Larry Coker's recruiting pitch included a note that he'd graduated all but two of his players at Miami. That caught Ron Davenport's attention. The NFL was still mostly a pipe dream. College football was mostly a means to earn an expensive diploma. It didn't hurt that he was a casual Miami fan during the early 2000s, when Coker brought a national title to Coral Gables.

As Signing Day drew closer, Marcus Davenport had his heart set on New Mexico.

"I don’t know where I’m going to send you, but it ain’t going to be that New Mexico," Ron Davenport recalls telling his son. "This may be the last decision I get to make for you. He texts me and says, 'I don’t want to go (to UTSA).' Two hours later, he says 'Dad, I thought about it, wherever you want to send me, I’ll just make the best of it. Later that day, he said, 'I’m good with whatever decision you make.'

Marcus Davenport was staying home, but his dad promised that a year later, they'd talk again. If UTSA wasn't the best place for him, he could transfer. That conversation was never necessary.

Davenport is a hair under 6-6 now and weighed in at 259 pounds at the Senior Bowl last month. Legend has it he was barely 6-3 and 198 pounds when he graduated high school. Though like most legends, it's slightly embellished.

"People like to say that because it's a better story. But he was taller. Probably like 6-4 or 6-5," Ron Davenport said. "And he was playing at like 210-215 in high school."

Davenport did, according to his dad, sprout from 5-8 or 5-9 to almost 6-2 in 12 months when he was 12.

But during his senior year of high school, football season gave way to basketball season, where he was his district's defensive player of the year. And then track season arrived, where Davenport threw the discus and shot put, as well as serving as the anchor leg for Stevens' mile relay team. His diet couldn't keep up with his metabolism. By the time he enrolled at UTSA, he was back under 200 pounds.

The Roadrunners planned on redshirting him, but preseason injuries forced him on the field. In his first game, on his 18th birthday that came more than two months earlier than his family had planned, he notched his first sack, bringing down Houston's John O'Korn in a shocking 27-7 UTSA upset over a Cougars team favored by two touchdowns.

Even as an undersized, lanky freshman defensive end, he made an impact with three sacks in 11 games. But after his sophomore year, Coker was fired for a 7-17 run over his final two seasons. The Roadrunners hired LSU associate head coach and running backs coach Frank Wilson, who loved what he saw when he arrived on campus.

"You saw glimpses of him having ability," Wilson said. "But he had a frail body. You were hopeful this kid had a future, but we didn’t see it as, 'We’ve got a future first rounder.'"

What he had was a 212-pound pass rusher who'd earned the semi-pejorative nickname, "Bambi," after the wide-eyed deer popularized in the Disney movie. Coker's staff loved his production, but his rail-thin frame and raw ability meant he'd be used as a motivational ploy for older players.

"If Bambi can do that, why can't you?!" coaches would yell.

Wilson made sure Davenport knew he couldn't take the field at 212 pounds by the time the 2016 season arrived. He didn't want a pass rusher. He wanted a versatile defensive lineman. That meant constant eating and trips home from the dining hall with four chicken sandwiches stuffed in a styrofoam container. He elected for fried chicken at first before shifting to grilled later on, piling them high with loads of lettuce and washing them down with a couple glasses of chocolate milk. By his junior season, he was up to 230.

In 2017, he played at nearly 260 pounds, fueling his rise up draft boards. By the end of his career in Wilson's program, Bambi was gone. Davenport was now known as "Sunday."

"He played at a level where he was unblockable at times. He’d get into third and long--the money down--and he’d say, 'It’s my down. I got us, Coach.' Then he’d go get a sack. That’s when you knew he knew he could be different," Wilson said. "But he hasn’t even tapped his potential. He’ll be a better pro than a college player."

The South team's practice at the Senior Bowl was over. Players mingled on the turf at Ladd-Peebles Stadium, chatting with NFL scouts and media assembled in the south end zone. Fans, young and old, lined the fence leading to the locker room on the stadium's west side. Da'Shawn Hand ducked into the shaded entry way and made his way underneath the bleachers.

Davenport jogged beside him.

———

David Ubben is the college football insider and editor for Dave Campbell’s Texas Football, and has written for ESPN, FOX Sports and The Athletic. Find him on Twitter: @davidubben.

This article is available to our Digital Subscribers.

Click "Subscribe Now" to see a list of subscription offers.

Already a Subscriber? Sign In to access this content.